Dictating Coverage Based on Offensive Field Position & Personnel

By James “Mac” McCleary Defensive Coordinator, Notre Dame High School (LA)

Researcher’s Note: This report was prepared by Coach James McCleary of Notre Dame High School (LA). McCleary shares his innovative way of instructing his defensive secondary to play coverage based on offensive spacing and personnel. It’s important to note that McCleary’s system is a “check system” made by his corners and safeties pre-snap and is entirely predicated on how and where an offense lines up its personnel. Although this may seem to be consuming to teach your players (he draws up 200 cards a week complete with detailed hash marks so his kids can make the proper calls), once it’s mastered your players develop a complete understand of how offenses plan on attacking spacing and leverage in a defense.

The ultimate goal of any defense is to take away what opposing offenses do best. Our philosophy at Notre Dame High School has been to use our fronts and coverages to do that. It is our desire to outflank offenses with these fronts and coverages. Anytime we defend an offense, we look at five key components of what offenses are doing:

- What type of formation is on the field?

- What part of the field are they placing formation?

- Which type of personnel is in the formation?

- Where is their best personnel lined up within the formation?

- What is the spacing between the receivers?

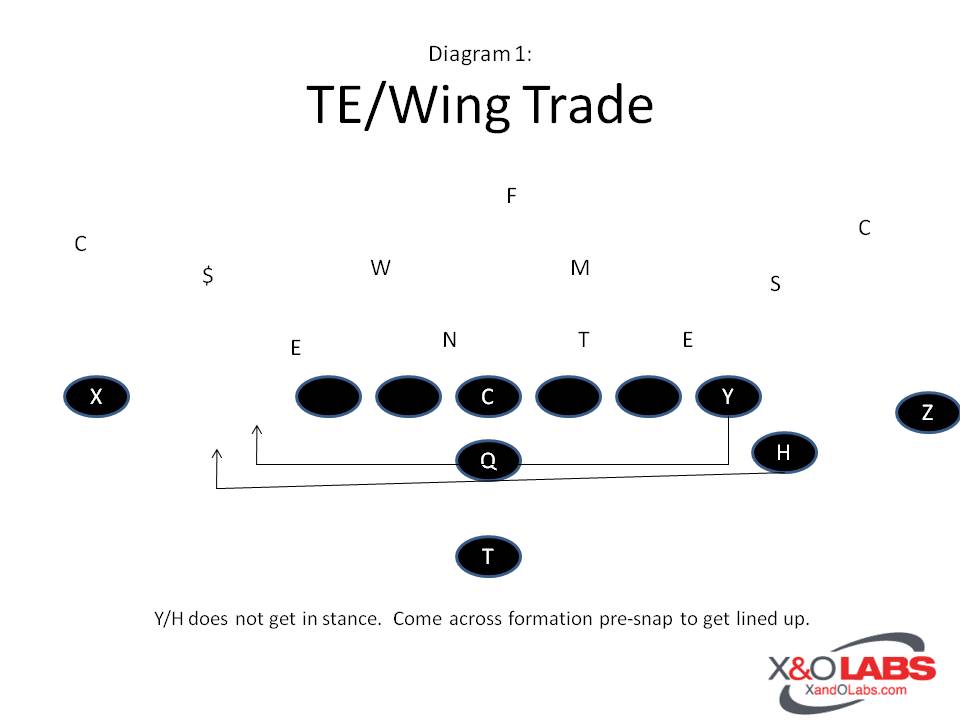

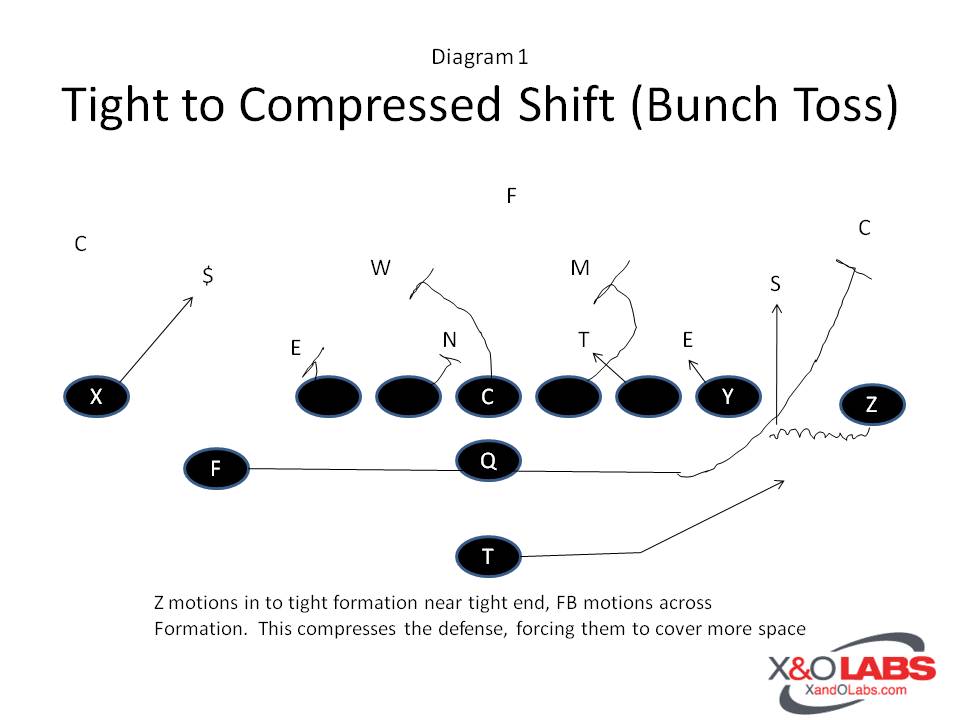

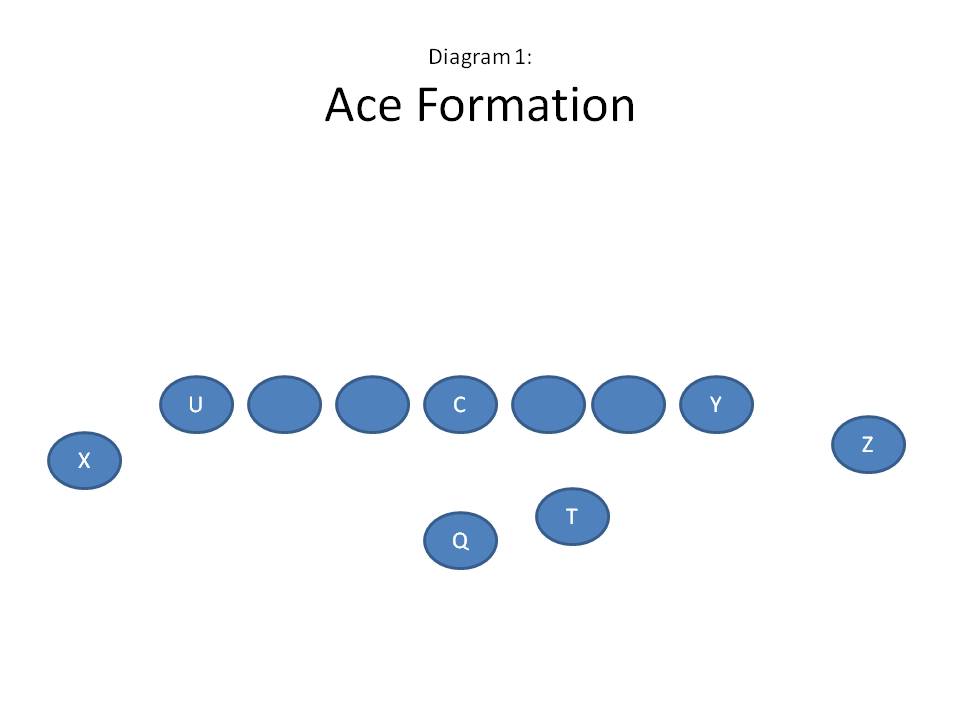

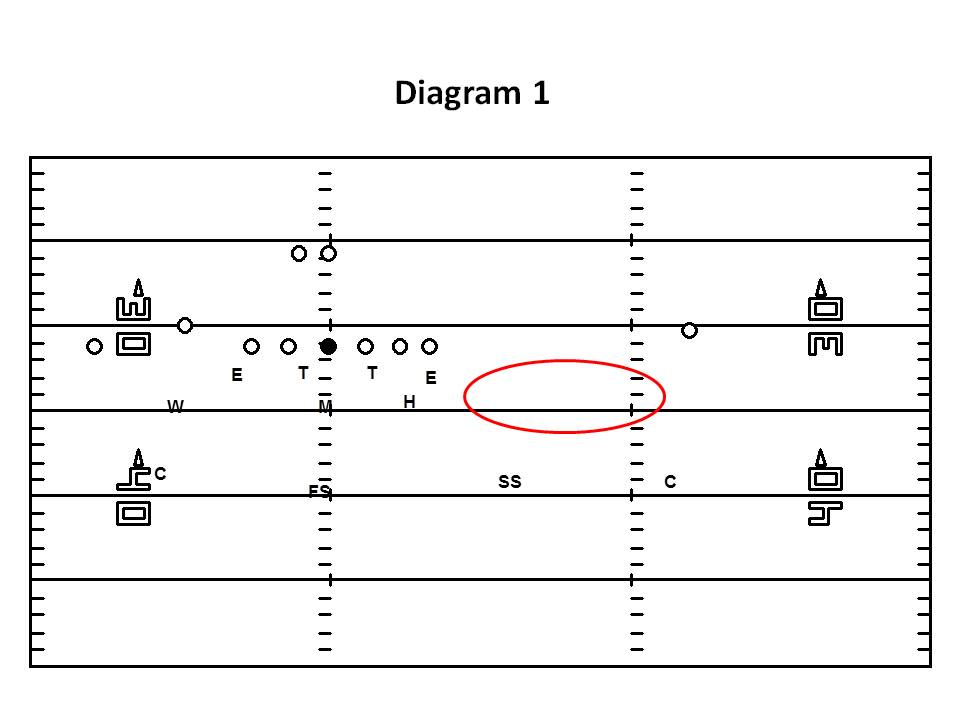

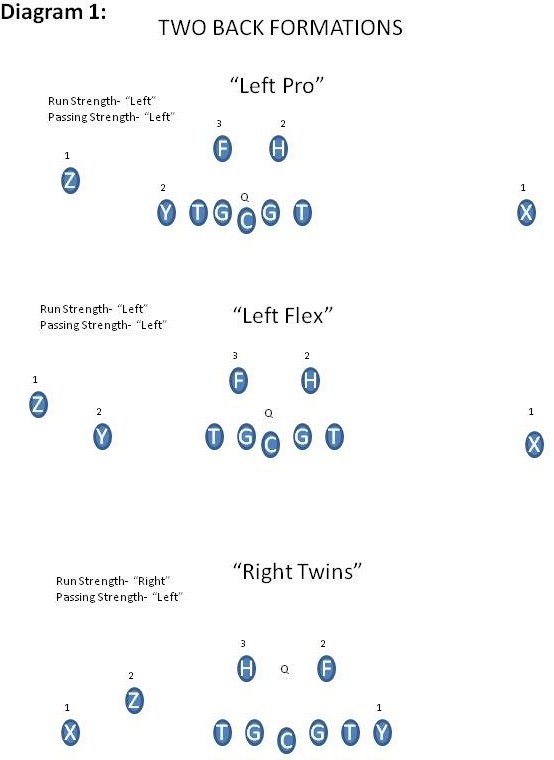

Spacing and Personnel We try to teach our kids the game by understanding receiver spacing and where QB’s want to throw the ball based on that spacing and personnel placement. For example: When looking at a formation with wide spacing of the receivers, we tell our players that the space in between is where they are looking to throw the ball (diagram 1).

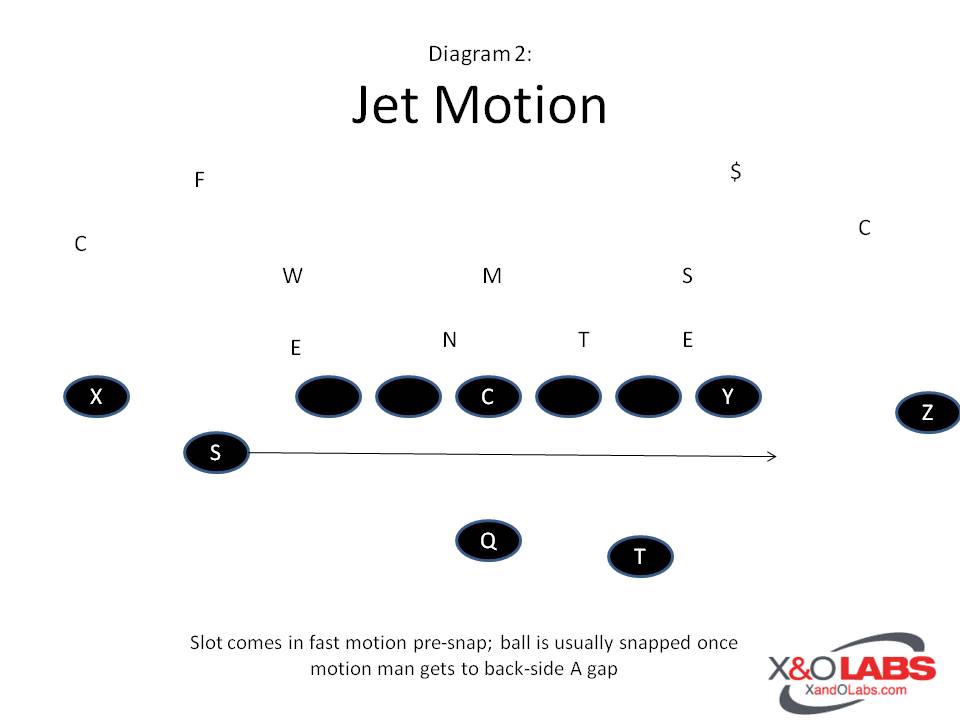

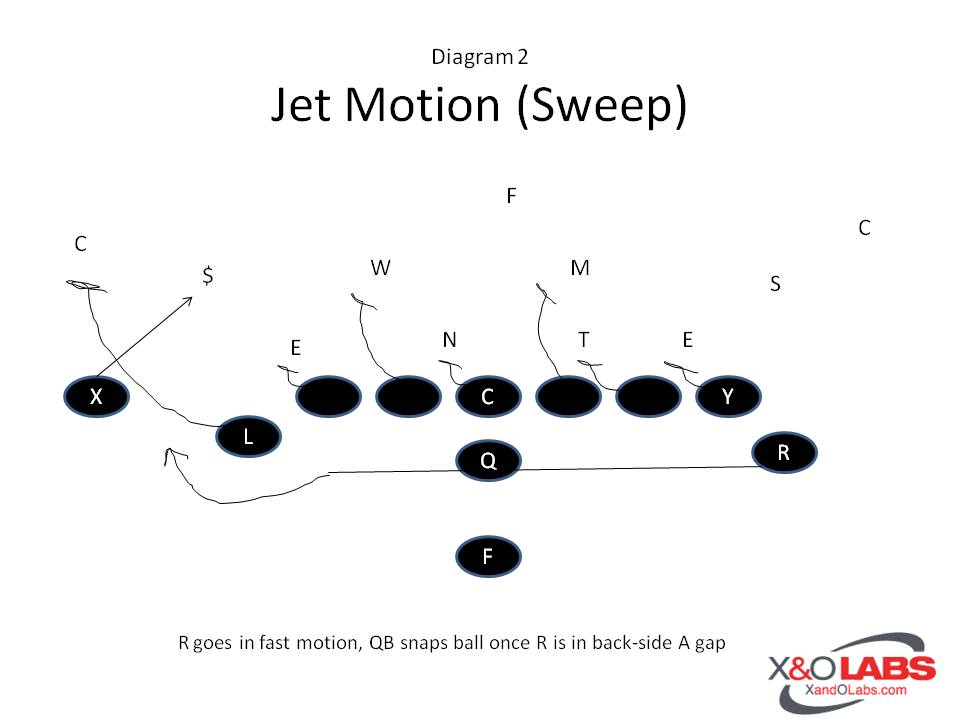

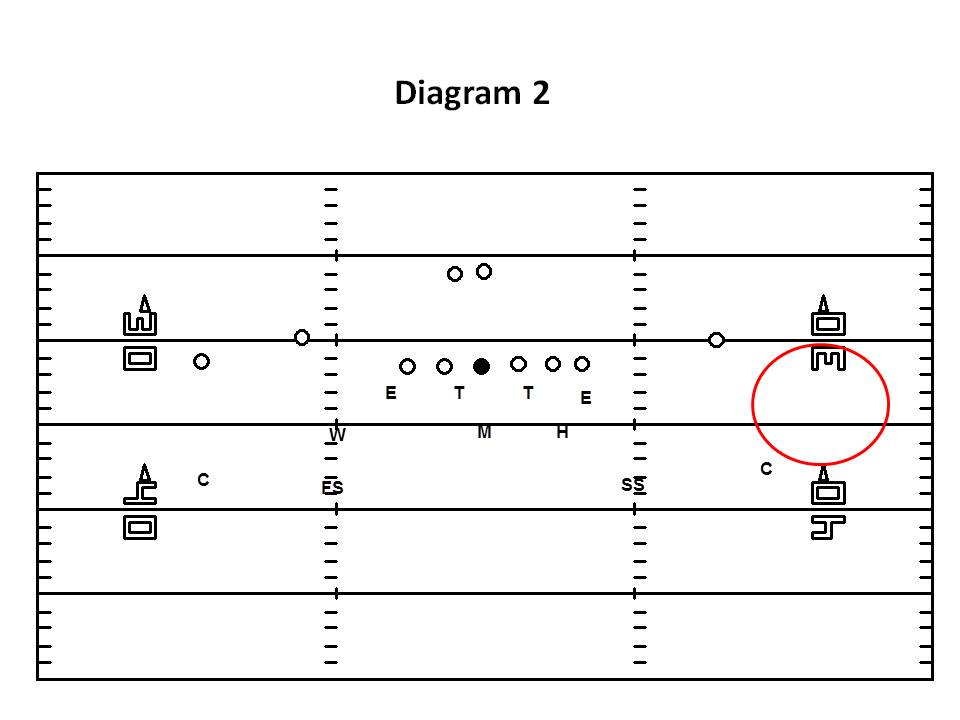

When formations have a receiver spacing that is tight, we tell them that they want to throw it to the space outside (diagram 2).

When defending offenses, the primary idea is to take away were they want to go by body position first. When an offense places its best personnel into the boundary, we tell the players that they will most likely throw the ball short into the boundary. When they are to the field, they will most likely throw wide to the field. An example of this is when we might be playing a team that throws a high percentage of screen passes. Usually, there is that one player that they like to move around the formation in order to get him the ball. We may get into a press position with the corners to get in his pocket on the inside screens to make it difficult for the blocker to pick him off on schemes such as rocket or bubble screens. Another example might be when we play a team with a significant vertical threat. We will make sure the coverage is designed so that there is always someone over the top of him.

Get X&O Labs’ new Research Reports sent directly to your email inbox. Sign up now, it’s FREE! In the right hand margin of this page >>>>>>>> above our Facebook box, there is a “Stay Informed!” email sign up box. Just enter your name and email and click the “GO” button.

Once you teach body position, now it’s necessary to design scheme to counter what offenses are doing. By teaching spacing and where the formation is on the field (middle or hash), the players become great predictors of what can happen, thus putting themselves in a position to take away what an offense wants to do just by lining up where offenses want to place the ball, and it’s our jobs as coaches to get us there. How we do this at Notre Dame High School is to have our corners and safeties change their alignment to take away the void areas (the space where they want to throw the ball) in the defense.

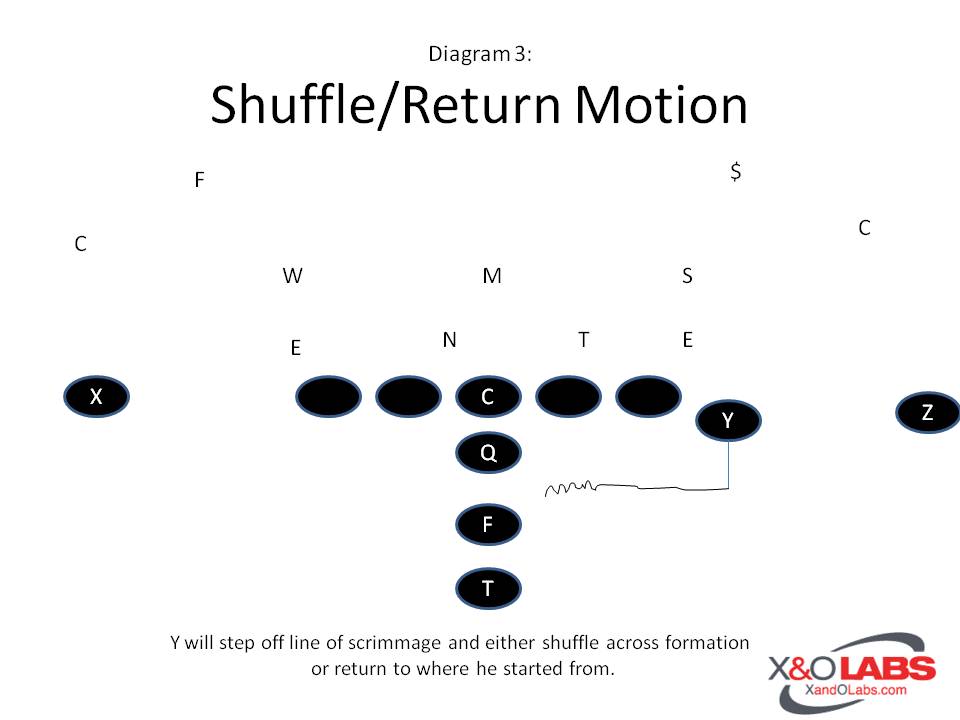

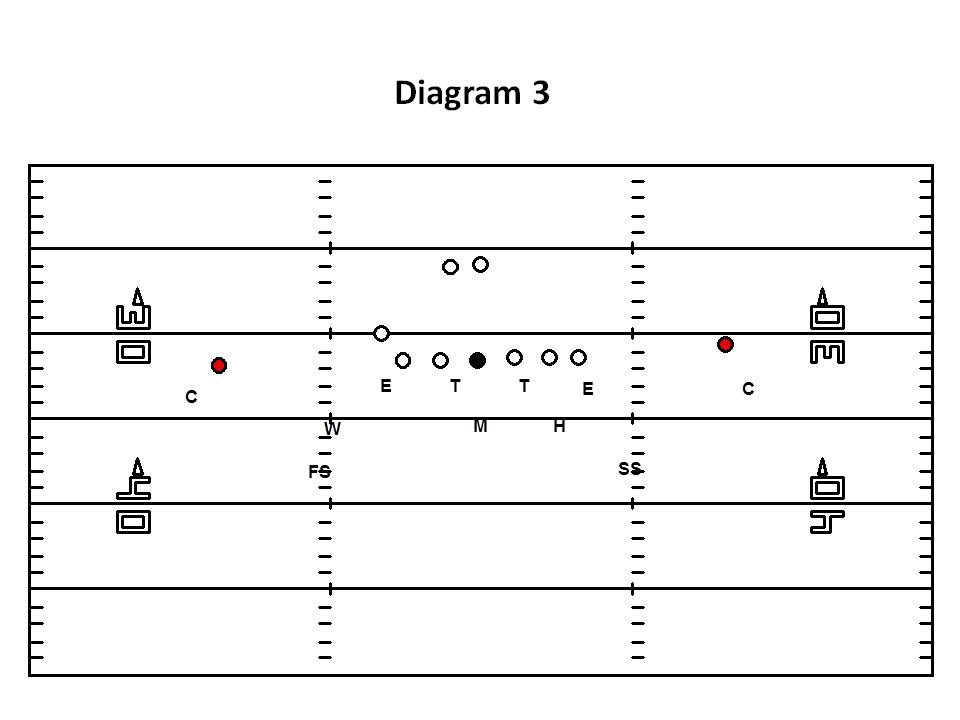

Take typical cover two for example, our corners will have three possible alignments that they can get into in cover two in order to take away what the offense wants to do. The first is the typical pressed outside leverage position. We use with average spacing of receivers to deny outside release and funnel to the safety (diagram 3).

The second spacing we will teach the corners are deep inside leverage or what we call choke technique (diagram 4). We use the choke technique when the receiver is on, or outside, the numbers. When a receiver is on, or outside the numbers there are only two things he can do. Go vertical or get inside. We take that away with our choke technique. Notice in diagram 4, we have taken his body position away just by lining up deep and inside. The corner still plays cover two, he just does it from a deep and inside leverage. He is now in a better position to take away any slant or vertical by his alignment.

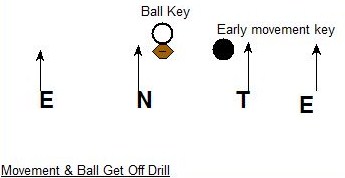

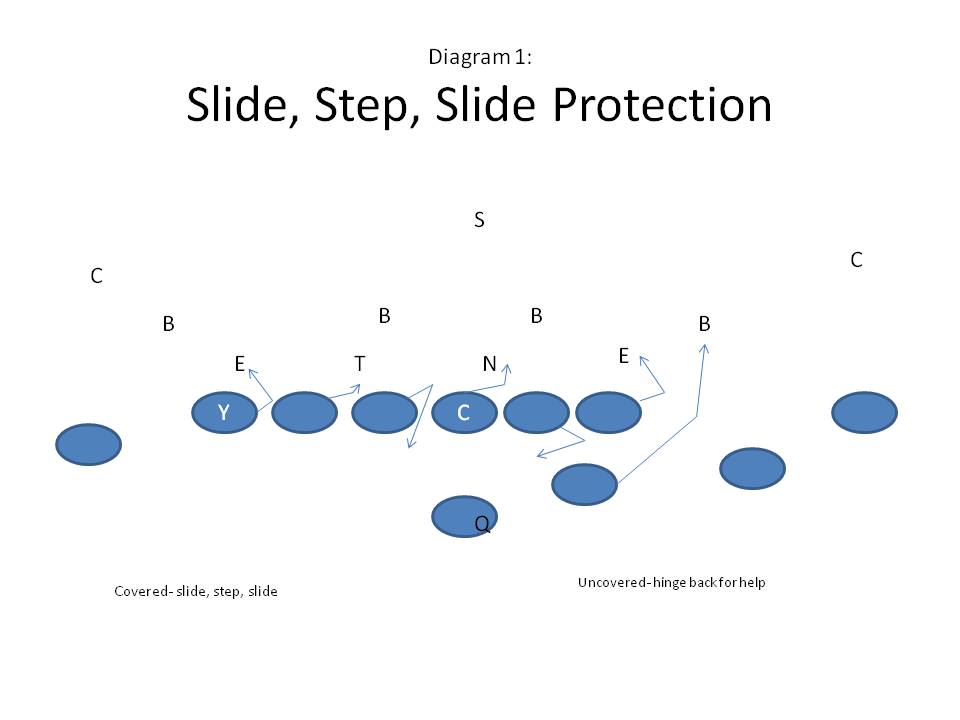

We start each drill with three things in mind that we hope the athletes carry over into games: alignment, stance, and key. Generally, when our safeties make a run call to their sides, they align at 8-10 yards deep, on the outside shade of the EMLOS; in most cases, this is a tight end or an offensive tackle, depending on the offensive set we see that week. For the stance, we ask our safeties to use a square stance, with knees and hips flexed, back slightly flat, hands loose in front of the body. During a run call, we want our safeties to keep their eyes out of the backfield. As a result, we tell them to key the EMOLS solely. We find that, in most cases in high school offenses, the tight end or open side offensive tackle tip off the type of play. At the snap of the ball, we tell our safeties take a couple pop steps in place as they key the EMLOS; this gets their feet moving without losing ground.

We start each drill with three things in mind that we hope the athletes carry over into games: alignment, stance, and key. Generally, when our safeties make a run call to their sides, they align at 8-10 yards deep, on the outside shade of the EMLOS; in most cases, this is a tight end or an offensive tackle, depending on the offensive set we see that week. For the stance, we ask our safeties to use a square stance, with knees and hips flexed, back slightly flat, hands loose in front of the body. During a run call, we want our safeties to keep their eyes out of the backfield. As a result, we tell them to key the EMOLS solely. We find that, in most cases in high school offenses, the tight end or open side offensive tackle tip off the type of play. At the snap of the ball, we tell our safeties take a couple pop steps in place as they key the EMLOS; this gets their feet moving without losing ground.

Conversely, if we are out-numbered at the point of attack the QB must recognize this as a bad situation and check the play into a more advantageous run or pass based on the game plan for that given week – our 3 vs. their 4 (See Diagram 2).

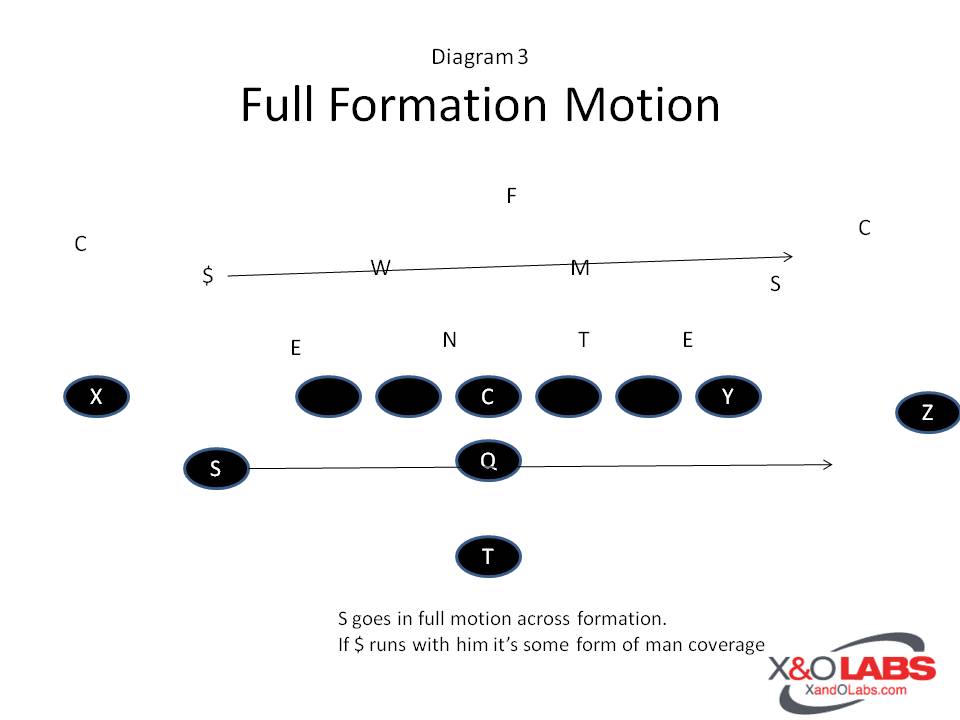

Conversely, if we are out-numbered at the point of attack the QB must recognize this as a bad situation and check the play into a more advantageous run or pass based on the game plan for that given week – our 3 vs. their 4 (See Diagram 2).  As I mentioned earlier, one way that you can account for that 4th defender is to create a four man surface to the play side by motioning into a 3×1 formation so that the slot receiver can account for that edge player (See Diagram 3).

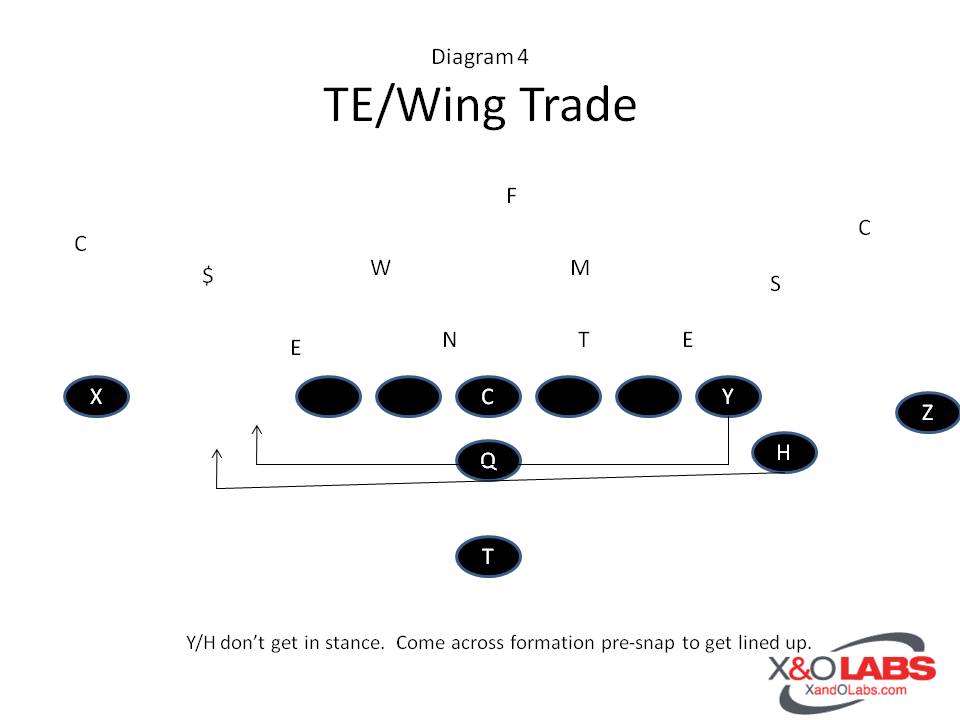

As I mentioned earlier, one way that you can account for that 4th defender is to create a four man surface to the play side by motioning into a 3×1 formation so that the slot receiver can account for that edge player (See Diagram 3).  You could also call the play out of a 3×1 formation to begin with, giving you a 4 man surface to work with right off the bat (See Diagram 4). If you have a slot WR that is a physical blocker this could be a great matchup for you, or it could be a nightmare if that guy isn’t willing to be physical blocking an OLB/Safety type player.

You could also call the play out of a 3×1 formation to begin with, giving you a 4 man surface to work with right off the bat (See Diagram 4). If you have a slot WR that is a physical blocker this could be a great matchup for you, or it could be a nightmare if that guy isn’t willing to be physical blocking an OLB/Safety type player.